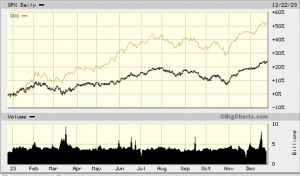

S&P500 (black) and QQQ i.e. Nasdaq-100 (orange), 22 Dec 2022 through 23 Dec 2023; courtesy BigCharts

Forecasters’ December 2022 predictions

On 20 December 2022, Bloomberg published the results of their annual survey of prominent market forecasters. The consensus: “Investors ready to turn the page on the worst year for equities since the global financial crisis should brace for more pain heading into 2023.”

In particular, the average target of 22 forecasters canvassed by Bloomberg on 20 Dec 2022 was that the S&P500 index of U.S. stocks would close December 2023 at 4078, or in other words with a modest 6.2% gain from the December 2022 close (3839.50). This 6.2% rise was midway between the most pessimistic prediction of a roughly 11% decline and the most optimistic prediction of a roughly 24% rise. [These figures have been adjusted slightly to reflect the 31 Dec 2022 close.]

At the time, numerous analysts had openly predicted a significant recession. Barclays Capital predicted that 2023 will go down as “one of the worst for the world economy in four decades.” Fidelity International stated that a hard landing looks “unavoidable.” J.P. Morgan’s team of analysts expected the S&P500 to “fall back toward the lows seen in 2022 before a pivot by the Fed fuels a second-half rebound.” The Bloomberg article mentioned above included a technical analysis chart, prepared by Bloomberg staff, with the title “Downtrend Intact / US stocks failed to overcome the trend line that had capped prior bear rallies.”

News headlines

Along this line, here are some of the prominent news stories of late 2022 and early 2023:

- In November 2022, the sudden collapse of FTX, transpiring over just a few days, stunned the crypto industry, which had long promoted itself as a high-tech means to avoid the risk of traditional banking.

- In December 2022, the U.S. Federal Reserve, defying pleas for mercy from politicians and investors alike, raised its Federal Funds Rate by 50 basis points, followed by 25 points in February 2023 and 25 points in March 2023.

- On 10 March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank, a lender to many tech firms, collapsed after a sudden bank run. It was soon followed by Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse.

- As former Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes pursued legal maneuvers to reduce her 11-year prison sentence, many analysts wondered how many other Silicon Valley tech firms were floating “fake it till you make it” claims.

- X (formerly known as Twitter) foundered after being bought out by Elon Musk. Microsoft laid off 10,000 workers. Meta, the parent of Facebook, laid off 10,000. Google laid off 12,000 employees via an email message.

- Major cities in the U.S. and elsewhere reeled from a huge jump in office space vacancy, threatening the solvency of commercial real estate. San Francisco’s office vacancy rate rose to 30%.

A December 2023 assessment of the December 2022 forecasts

Although 2023 is not quite over [as of 23 Dec 2023], it is time to assess the accuracy of the forecasts canvassed by Bloomberg in December 2022, and to compare this year’s record with that of previous years. The verdict? As the Economist explains, “Shareholders have had a remarkably good year. Forecasters have had a terrible one.” Jeff Sommer of the New York Times notes the following:

- As of 23 Dec 2023, the S&P 500 is at 4754.63, up an impressive 23.8% from the December 2022 close (3839.50), which represents a huge 17.6 percentage point gap from the consensus December 2022 forecast of a 6.2% increase, mentioned above.

- In 2022, the average forecast was for a 3.9% increase; the actual S&P500 lost 19.4%, for a whopping 23.3 percentage point gap.

- In 2018, the average forecast was for a 7.5% rise; the actual S&P500 fell 6.9%, a 14.4 percentage point gap.

- In 2008, the median forecast was for a rise of 11.1%; the actual S&P500 fell 38.5% — a staggering error of 49.6 percentage points.

- Based on data recently updated to 2023 by Paul Hickey of Bespoke Investment Group, Sommer found that from 2000 through 2023, the median Wall Street forecast missed its target by an average of 13.8 percentage points.

Somer concludes, “Wall Street strategists make predictions anyway, despite a track record that is extraordinary in its ineptitude.”

Denitsa Tsekova, Carly Wanna and Lu Wang of Bloomberg elaborated on the widespread failure of forecasts for the first half of 2023 in particular:

Stocks rallied when they were forecast to tumble, expected bond gains fizzled, and the recession never came. … Up and down Wall Street, forecasters were caught flat-footed by how the first half of 2023 unfolded in financial markets.

Paul Krugman, Nobel Prize-winning economist and New York Times columnist, added, “I can’t think of another example in which there was such a universal consensus that recession was imminent, yet the predicted recession failed to arrive.”

Along this line, Nir Kaissar analyzed a set of predictions by market forecasters over a 17-year period from 1999 through 2016. He found that although there was a modest correlation between the average forecast and the year-end price of the S&P 500 index for the given year, these predictions were surprisingly unreliable during major shifts in the market. For example, Kaissar found that the strategists overestimated the S&P 500’s year-end price by 26.2 percent on average during the three recession years 2000 through 2002, yet they underestimated the index’s level by 10.6 percent for the initial recovery year 2003. A similar phenomenon was seen in 2008, when the strategists in his study overestimated the S&P 500’s year-end level by a whopping 64.3 percent in 2008, but then underestimated the index by 10.9 percent for the first half of 2009. In other words, as Kaissar lamented (independently of Hickey, Sommer and others), the forecasts were least useful when they mattered most.

Our analysis of market forecasters

In 2017, the present author, together with three other colleagues, completed an analysis of the records of prominent U.S. market forecasters. For this study, we expanded on a 2013 study conducted by the CXO Advisory Group, which ranked 68 forecasters. We analyzed these 68 forecasters based on two additional factors: (a) the time frame of the forecast (forecasts are categorized as up to one month, up to three months, up to nine months or beyond nine months); and (b) the importance and specificity of the forecast.

The results of our analysis are available in this technical paper. The average score was 48% — i.e., not significantly different from chance. Among the 68 forecasters in our study were 27 who employ technical analysis in their work. So how well did these 27 technical analysts do? Their average prediction score was 44.1%, slightly less than the average of all 68 forecasters in our study. In other words, there is no evidence whatsoever in these data that these forecasters can predict better than chance. If anything, our results must be on the optimistic side, because of the well-known survivorship bias phenomenon — very likely numerous unsuccessful forecasters have dropped out of the business, and thus are absent from our data.

What should individual investors do?

All of this once again raises the question of why so many investors, professionals as well as individuals, are willing to accept the advice of chart watchers and market forecasters, many of whom employ only mathematically unsophisticated tools (note the “technical analysis” chart in the Bloomberg report mentioned above), particularly when their past record of predictions is unambiguously poor?

As we have explained in earlier articles, one should not be too surprised at these findings, since they are a straightforward implication of the efficient market hypothesis (see also this report and this interview): In an era where markets are increasingly dominated by large, mathematically sophisticated, machine-learning-powered players with huge computer systems and datasets, it is virtually impossible for relatively unsophisticated forecasters and investors to consistently beat the markets. The efficient market hypothesis has some weaknesses, but beating the market say based on market psychology requires that one has a superior grasp of mass psychology effects in financial markets, which can hardly be assumed by individual forecasters, let alone by individual investors.

So what do writers such as Sommer and leading experts in the field recommend, particularly for individual investors with their 401K and IRA accounts? As we have emphasized before in these articles, the majority of individual investors would do well to simply follow the advice of Vanguard Funds founder Jack Bogle, Berkshire Hathaway founder Warren Buffett and Dimensional Fund Advisors co-founder David Booth: invest in one or a handful of low-cost index funds (or, alternatively, a modest-sized diverse collection of individual stocks and/or bonds), selected according to a sober analysis of appropriate risk and time frame, perhaps with the assistance of a qualified professional, and, most importantly, hold these investments for the long term — studiously avoiding the temptation to buy or sell based on day-to-day market fluctuations or commentaries.

As David Booth commented, “We don’t try to forecast the future. … We have no ability to do it. Nor does anyone else.”