Life expectancy, 1770-2023; source: Our World in Data

Target date funds

“Target-date funds” are currently the rage in the finance world. The term refers to a mutual fund that targets a given retirement date, and then steadily shifts the allocation of assets from, say, a 80%/20% mix of stocks and bonds at the start to, say, a 30%/70% or 20%/80% mix as the target date approaches.

Vanguard Group, which manages over USD$5 trillion in assets, much of it in employer-offered defined contribution retirement plans, reports that participation in its target date offerings have grown explosively in the past few years. In 2005, when Vanguard started offering target-date funds, only a few of their contracting organizations offered them, and only about 2% of covered individuals participated. Today, by contrast, over 90% of these organizations offer target-date funds, and over 75% of plan participants use them. Many participants invest their entire account in a single target-date fund.

Separately, Morningstar reports that at the end of 2024, over USD$4 trillion was invested in target-date funds. These assets have grown at a compounded rate of more than 30% annualized over the past 15 years.

The 60%/40% and 4% rules of investing

The rise of target-date funds raises the question of what is really the best balance of investments between equities and bonds, and how this mix should change over an individual’s career or lifetime. One commonly used rule is that the percentage of one’s portfolio allocated to equities should not exceed 100 minus one’s age. Thus while a 20-year-old could invest 80% of her savings in stocks, this should not exceed 30% by the time she reaches 70. Some have suggested replacing 100 by a higher figure, such as 110, but others argue that it should be reduced.

Another widely used rule of thumb is that a retiree should initially draw down no more than 4% of her total nest egg per year. Along this line, the U.S. firm Charles Schwab recommends this schedule:

| Time horizon | Asset allocation | Initial withdrawal rate |

|---|---|---|

| 30 years | Moderate (60% stocks/40% bonds-cash) | 3.8% to 4.4% |

| 20 years | Moderately conservative (40% stocks/60% bonds-cash) | 5.4% to 5.9% |

| 10 years | Conservative (20% stocks/80% bonds-cash) | 10.2% to 10.6% |

Increasing life expectancy

One key variable here is life expectancy. We often forget how much this has already increased: global average life expectancy has soared from 29 as recently as 1880 to 72 today (see graph above). This not a misprint! It is worth pointing out that the current global figure (72) is higher than that of the wealthy nations of North America and Western Europe as recently as 1970. Virtually every nation for which reliable statistics are available has seen a significant rise in life expectancy over the past 30 years.

In the U.S., although there have been some reversals (e.g., during the recent Covid-19 pandemic), life expectancy has risen fairly steadily, from 67(male)/72(female) in 1950 to 73(male)/79(female) in 2022. The U.S. Social Security Administration and the Census Bureau estimate that by 2050, the life expectancy of females will rise to 83-85, and that of males will rise to 80. A separate study by the MacArthur Research Network estimates even higher U.S. figures: 89-94 for females and 83-86 for males. Life expectancy figures are comparable or even higher in other first-world nations (84 in Hong Kong, Japan and Italy, for example).

Even with relatively conservative projections of longevity, it is clear that an increasing fraction of humanity will live to 100 and beyond. In the U.S., the over-100 age bracket is expected to hit 6 million by 2050, growing 20 times as fast as the overall population.

While many factors are at work, one reason for these increasing longevity figures is the remarkable development of effective medications and treatments for numerous debilitating medical conditions. Out of many examples that could be mentioned, recently developed GLP-1 agonist drugs such as Ozempic and Wegovy have astonished the medical community by their effectiveness not only against diabetes (which is a major achievement), but also against obesity, heart attack, stroke, alcoholism and kidney failure. They may also slow cognitive decline due to Alzheimer’s disease.

Longevity research

While not yet widely recognized, numerous research organizations are looking into the mechanisms of aging and death, with the bold long-term objective of not just accepting these eventualities as inevitable consequences of mortality, but instead as merely technical “bugs” awaiting fixes. Google, for instance, has allocated hundreds of millions of dollars to fund an anti-aging spinout named Calico. Its mission statement reads:

Calico is a research and development company whose mission is to harness advanced technologies to increase our understanding of the biology that controls lifespan. We will use that knowledge to devise interventions that enable people to lead longer and healthier lives. Executing on this mission will require an unprecedented level of interdisciplinary effort and a long-term focus for which funding is already in place.

Calico is led by noted longevity researcher Cynthia Kenyon, who 20 years ago showed that by merely altering a single DNA letter in its genome, a laboratory roundworm could live six weeks instead of just three.

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos has joined other investors to fund Unity, a San Francisco startup developing drugs aiming at ridding the body of “senescent” cells. Along this line, researchers recently found that a “cocktail” of three drugs appeared to rejuvenate the human body, stopping or turning back certain biological clocks (see also this New Scientist report).

Some researchers are even more expansive, saying that it is inevitable that aging and death will eventually be conquered. As Israeli scholar Yuval Harari recently wrote, by 2050 some humans may become a-mortal, in the sense that in the absence of fatal trauma their lives could be extended indefinitely. At present, we have no way of knowing how soon these research efforts will truly pan out. But given all of the activity in this arena, it seems very foolish to dismiss or reject the possibility of significant breakthroughs that could significantly impact modern society.

Financial consequences of increasing longevity

Given even the relatively conservative projections of life expectancy, it is clear that we need to start asking some hard questions about prevailing investment rules, such as those mentioned above. Do these rules, which are so commonly used in the investment world, really make sense in today’s world of rapidly advancing science and technology?

After all, a person who retires at 65, and who expects to live to 85, will have to subsist for 20 years on savings, supplemented as usual by some Social Security benefits or the equivalent in other nations. But given current projections, she might be so fortunate as to live to 95 or beyond 100, which is 35-45 years on savings. Even if she decides not to retire at 65, but instead waits until 70, she may spend 30 years or more living on retirement savings. Her savings will not only have to last much longer, but in addition will need to continue growing for a long time to meet her expected financial requirements and to compensate for future inflation (an important consideration in today’s volatile geopolitical climate).

The recent financial independence / retire early (FIRE) movement raises some closely related issues. FIRE refers to the plans of a small but growing fraction of the public to live relatively meagerly, save a large fraction of their income, and then retire when their nest egg is, say, 25 times as large as a basic living income, hopefully at a rather young age, such as 35 or 40. There are numerous difficulties with such a plan, including: (a) one would forfeit much of one’s Social Security benefit or its equivalent in other nations; (b) it may be necessary to relocate to a very low cost-of-living (and perhaps not particularly desirable) locale, possibly even in another nation; (c) raising a family and supporting children through college may be out of the question; (d) one may need to forego the possibility of world travel and other common perks of retirement; and (e) one may need to deal with known mental health issues in having lots of time and relatively little meaningful, challenging work to do (lay on a beach all day and get sunburned drinking mai-tais?).

But a larger concern, in an era of steadily increasing longevity, is that a person “retiring” at age 35 or 40 will need to rely on savings not just 20 years, but more likely 40, 50, or even 60 years. Is this a truly realistic plan, particularly if one’s nest egg is invested relatively conservatively?

Time to rethink the equity/bond and target date formulas?

Given any of the above considerations, let alone all of them, it seems clear that both individual and institutional investors need to reconsider their investment portfolios in light of the emerging brave new world where people live significantly longer than they do today.

In particular, perhaps individual investors should be advised to remain in an all- or mostly-equity portfolio longer into their careers and, depending on circumstances, perhaps even after retirement. One can never guarantee that current equity returns will continue indefinitely in the future, but given over a century of experience in modern financial markets, the compounded return of equities with reinvested dividends very likely will exceed that of a bond-dominated portfolio over any reasonably long-term horizon.

In particular, perhaps individual investors should be advised to remain in an all- or mostly-equity portfolio longer into their careers and, depending on circumstances, perhaps even after retirement. One can never guarantee that current equity returns will continue indefinitely in the future, but given over a century of experience in modern financial markets, the compounded return of equities with reinvested dividends very likely will exceed that of a bond-dominated portfolio over any reasonably long-term horizon.

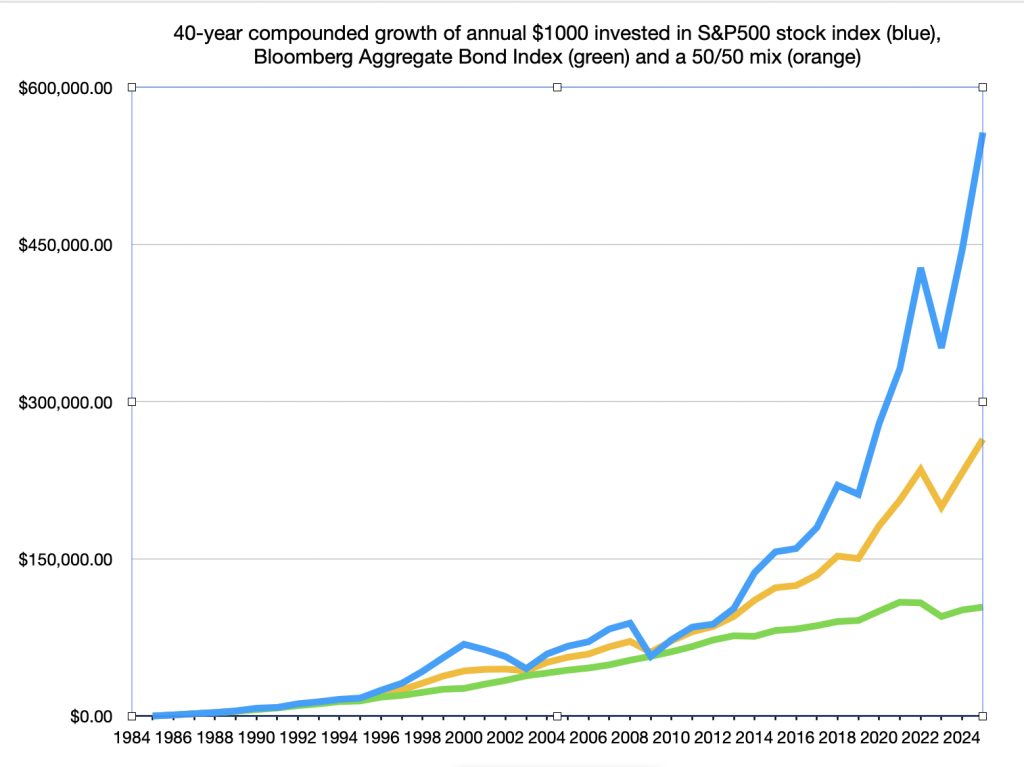

The graph at the right compares the growth of an annual USD$1,000 investment in the S&P 500 stock index with reinvested dividends (blue); the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (green), and a 50/50 mix (orange) over the 40-year period from January 1985 through December 2024 (note that this includes the “lost decade” of 2001-2010, when U.S. equities performed very poorly). At the end date (2024), the S&P 500 investment program has grown to $556,000, whereas the all-bond program has only reached $103,000 and the 50/50 program has only reached $264,000. These are not minor differences!

Conclusions

Any discussion of such issues must of course include the disclaimer that “past performance does not guarantee future results”: no one can pretend to possess a crystal ball to forecast the future of national or world financial markets. Indeed, we have in numerous articles on this forum highlighted the folly of attempting to forecast market prices (see HERE as a single example). And a significant market correction could begin at any time.

Further, we should emphasize that the discussion above pertains to long-term retirement investment. Certainly other circumstances (e.g., saving for the downpayment on a home or a teen’s future college education) warrant different investment strategies.

But with those caveats aside, it is abundantly clear that equities out-perform fixed-income investments over most long-range time horizons. Thus, as we have emphasized above, given the increasing longevity of the human population, many individual investors (particularly in younger age brackets) need to carefully consider the long-term performance of their retirement savings portfolios.

Indeed, how individuals, pensions, mutual funds and even government retirement systems (e.g., Social Security) deal with the phenomenon of increasing longevity may well emerge as one of the most important issues of our time.

[Note: The present author acknowledges the assistance of ChatGPT-5 in obtaining historical market data that is the basis for the above chart. Also, this article is based on part on a previous Mathematical Investor article.]